Dogwitch by Catherine Rockwood (Bottlecap Press, 2025). 28 pages. $10

As family lore goes, I was a little girl who required an extensive collection of dog stuffies arranged around me in order to sleep at night—read it as childhood quirk or beginner’s attempt at protection spell—but it portended a significant and lifelong affinity for dogs. Through childhood, adolescence, college, marriage, motherhood, and midlife, I’ve always lived alongside as few as one and as many as nine actual dogs at a time. Purebreds, street dogs, strays, ferals, fosters, and rescues, these were not just dogs in the background but dogs as close companions with individual personalities and with whom I shared a spectrum of integral bonds. Anyone who knows me knows I’ve never met a dog I didn’t like (often more than most humans), and I guess so does Instagram, because I was drawn to Catherine Rockwood’s chapbook, Dogwitch, the moment my feed served it up to me.

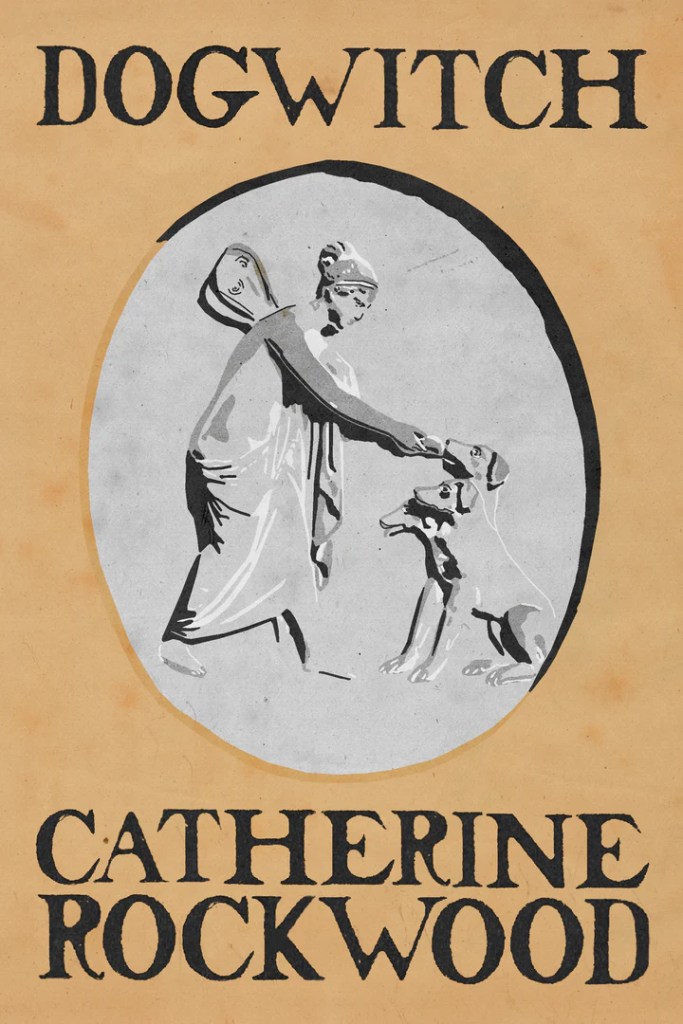

Dogwitch’s cover features Bertel Thorvaldsen’s relief of Psyche and Cerberus, immediately suggesting mythic encounter between woman and animal. Thorvaldsen’s work signals shadow and trial, both of which follow in Rockwood’s poems; but it also depicts a tentative sense of connection and understanding between Psyche and Cerberus, as she bends and reaches to offer him the honeyed cake and, though monster, he receives it in the posture of a loyal hound.

While so many literary representations of dog ownership lean on cliche and sentimentality, Rockwood’s poems resist those pitfalls and captivate their reader by focusing on a mutual guardianship between “difficult” woman and dangerous dog. I use quotes around “difficult” because it’s a slippery, othering label often used to describe and weaponize any shade of female nonconformity—social, behavioral, sexual, psychological, etc.—but one that is essential in understanding the external judgement leveled at the speaker of these poems. Rockwood’s speaker is not sorry, doesn’t always trust her impulses, and owns her furies, questions, and appetites. In “A Tinderbox Itself is Innocent,” she writes, “some people meet me and back away stiff-legged / senses thrumming.” She is “too much” in a way that, at least to this midlife reader, feels relatable.

Similarly, the dogs in these pages are not the adorable, endearingly-derpy, or easy-to-love pets that strangers walking down the street might stop to coo over; these are dogs with pasts, with teeth, with pointed muscle. I loved the attention to animal physicality in these poems. In “The fifth thing,” Rockwood writes:

A hound is a moving sculpture of appetite.

I cherish the points of their cheekbones, almost as sharp

as the white teeth that lie behind generous curtains of muzzle

above long jaws with flews like opera capes.

Where you like to see excess expressed is a personal thing.

I prefer when it’s pointing toward the gullet.

In Dogwitch both speaker and subject are creatured by danger, violence, betrayal, and cruelty; experience teaches them their capacity to both survive and inflict damage. But in their shared vulnerability and wariness, they attach to each other with a fierce loyalty and protection. One of my favorite examples of this is in “Ode to Meanness,” where Rockwood writes:

O, Meanness! Generations

of dirt-wall cellars and the rusted nail

inside loose shingle rise to your clenched fists.

The bone-marked cur that mauls

the well-fed hand now looks to you

with frightening devotion.

Later, in “Familiar,” the first of several poems considering the relationship between witch and familiar, Rockwood writes:

It does not always have to drink your blood.

It can be a live thing watchig

what you honor, what you defile.

If the trope of dog as man’s best friend suggests a kind of human-animal connection that results in obedience, Rockwood’s “Familiar” series subverts that expectation by portraying an edgier telepathy between woman and hound. Under such a bond, every flicker of distrust, rage, or resentment gets transmitted immediately, just as it would between witch and familiar. Think dog as hygrometer calibrated for storm-turn, dog as live wire volta. If it is a strangely gratifying kindredness, Rockwood is aware that it’s also practically inconvenient to have your dog knowing and acting according to your darker, otherwise un-telegraphed thoughts, just as it can be a weight to understand and manage theirs.

In “To the Witch of Edmonton, her Familiar’s Love,” Rockwood writes:

no slight malignant thought, Elizabeth,

could dwell with thee a minute ‘fore I knew

(so close and apt did my soul hang on thine)

and then what thou hadst frowned on I would seek

to havoc

This psychic attunement works as a powerful engine of action and empathy in Dogwitch. In “For Abandoned Pets,” rabbits, cats, and a hound are rescued by sisters asking themselves if they’ve “learned / how to love a fearsome high-ribbed creature/running after trust that flees her.” In “Anti-Catechism,” the speaker frenzies, questions a higher power, and risks injury while attending to “a beautiful / feral dog [she’s] trying to fucking save” after it has poisoned itself with “a half a pound / of strong dark chocolate stolen from the counter.” Even though “Anti-Catechism” is threaded with irreverence and skepticism, I love the way it gives form to devotion in adverse conditions.

In the face of the hopelessness that marks our modern lives, Dogwitch is marked by an insistent urge to be present, perceive, and try our damnedest to save difficult, dangerous creatures anyway. The speaker knows the total achievement of this is impossible, and Rockwood’s reader knows the same, yet there is a significant sense of grace baked into the attempt.

We live in a world full of incomprehensible trouble and cruelty, and in a world where a close-to-unconditional love between species is possible. Rockwood writes “[In] all the starving world…Dogs love / where they are beloved. It is our doom / thus to be moved.” Full as it is of “cursed and glorious dogs” and their humans, “good days and ruin,” Dogwitch makes perfect reading for this incongruence.

Violeta Garcia-Mendoza is the author of Songs for the Land-Bound (June Road Press)—a 2025 National Indie Excellence Award finalist, 2025 Eric Hoffer Award honorable mention, and 2025 First Horizon Award finalist. In 2022, she received a grant from the Sustainable Arts Foundation for her poetry. Violeta’s work has appeared in Sugar House Review, The Dodge, RHINO, SWWIM, Psaltery & Lyre, and elsewhere. Violeta lives with her family on a small certified wildlife habitat in suburban western Pennsylvania.

Catherine Rockwood (she/they) reads and edits for Reckoning Magazine. Two chapbooks of their poetry, Endeavors to Obtain Perpetual Motion and And We Are Far From Shore, are available from The Ethel Zine Press, and a third chapbook, Dogwitch from Bottlecap Press.